Bloch-Redfield master equation¶

Introduction¶

The Lindblad master equation introduced earlier is constructed so that it describes a physical evolution of the density matrix (i.e., trace and positivity preserving), but it does not provide a connection to any underlaying microscopic physical model. The Lindblad operators (collapse operators) describe phenomenological processes, such as for example dephasing and spin flips, and the rates of these processes are arbitrary parameters in the model. In many situations the collapse operators and their corresponding rates have clear physical interpretation, such as dephasing and relaxation rates, and in those cases the Lindblad master equation is usually the method of choice.

However, in some cases, for example systems with varying energy biases and eigenstates and that couple to an environment in some well-defined manner (through a physically motivated system-environment interaction operator), it is often desirable to derive the master equation from more fundamental physical principles, and relate it to for example the noise-power spectrum of the environment.

The Bloch-Redfield formalism is one such approach to derive a master equation from a microscopic system. It starts from a combined system-environment perspective, and derives a perturbative master equation for the system alone, under the assumption of weak system-environment coupling. One advantage of this approach is that the dissipation processes and rates are obtained directly from the properties of the environment. On the downside, it does not intrinsically guarantee that the resulting master equation unconditionally preserves the physical properties of the density matrix (because it is a perturbative method). The Bloch-Redfield master equation must therefore be used with care, and the assumptions made in the derivation must be honored. (The Lindblad master equation is in a sense more robust – it always results in a physical density matrix – although some collapse operators might not be physically justified). For a full derivation of the Bloch Redfield master equation, see e.g. [Coh92] or [Bre02]. Here we present only a brief version of the derivation, with the intention of introducing the notation and how it relates to the implementation in QuTiP.

Brief Derivation and Definitions¶

The starting point of the Bloch-Redfield formalism is the total Hamiltonian for the system and the environment (bath): \(H = H_{\rm S} + H_{\rm B} + H_{\rm I}\), where \(H\) is the total system+bath Hamiltonian, \(H_{\rm S}\) and \(H_{\rm B}\) are the system and bath Hamiltonians, respectively, and \(H_{\rm I}\) is the interaction Hamiltonian.

The most general form of a master equation for the system dynamics is obtained by tracing out the bath from the von-Neumann equation of motion for the combined system (\(\dot\rho = -i\hbar^{-1}[H, \rho]\)). In the interaction picture the result is

where the additional assumption that the total system-bath density matrix can be factorized as \(\rho(t) \approx \rho_S(t) \otimes \rho_B\). This assumption is known as the Born approximation, and it implies that there never is any entanglement between the system and the bath, neither in the initial state nor at any time during the evolution. It is justified for weak system-bath interaction.

The master equation (1) is non-Markovian, i.e., the change in the density matrix at a time \(t\) depends on states at all times \(\tau < t\), making it intractable to solve both theoretically and numerically. To make progress towards a manageable master equation, we now introduce the Markovian approximation, in which \(\rho(s)\) is replaced by \(\rho(t)\) in Eq. (1). The result is the Redfield equation

which is local in time with respect the density matrix, but still not Markovian since it contains an implicit dependence on the initial state. By extending the integration to infinity and substituting \(\tau \rightarrow t-\tau\), a fully Markovian master equation is obtained:

The two Markovian approximations introduced above are valid if the time-scale with which the system dynamics changes is large compared to the time-scale with which correlations in the bath decays (corresponding to a “short-memory” bath, which results in Markovian system dynamics).

The master equation (3) is still on a too general form to be suitable for numerical implementation. We therefore assume that the system-bath interaction takes the form \(H_I = \sum_\alpha A_\alpha \otimes B_\alpha\) and where \(A_\alpha\) are system operators and \(B_\alpha\) are bath operators. This allows us to write master equation in terms of system operators and bath correlation functions:

where \(g_{\alpha\beta}(\tau) = {\rm Tr}_B\left[B_\alpha(t)B_\beta(t-\tau)\rho_B\right] = \left<B_\alpha(\tau)B_\beta(0)\right>\), since the bath state \(\rho_B\) is a steady state.

In the eigenbasis of the system Hamiltonian, where \(A_{mn}(t) = A_{mn} e^{i\omega_{mn}t}\), \(\omega_{mn} = \omega_m - \omega_n\) and \(\omega_m\) are the eigenfrequencies corresponding the eigenstate \(\left|m\right>\), we obtain in matrix form in the Schrödinger picture

where the “sec” above the summation symbol indicate summation of the secular terms which satisfy \(|\omega_{ab}-\omega_{cd}| \ll \tau_ {\rm decay}\). This is an almost-useful form of the master equation. The final step before arriving at the form of the Bloch-Redfield master equation that is implemented in QuTiP, involves rewriting the bath correlation function \(g(\tau)\) in terms of the noise-power spectrum of the environment \(S(\omega) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty d\tau e^{i\omega\tau} g(\tau)\):

where \(\lambda_{ab}(\omega)\) is an energy shift that is neglected here. The final form of the Bloch-Redfield master equation is

where

is the Bloch-Redfield tensor.

The Bloch-Redfield master equation in the form Eq. (5) is suitable for numerical implementation. The input parameters are the system Hamiltonian \(H\), the system operators through which the environment couples to the system \(A_\alpha\), and the noise-power spectrum \(S_{\alpha\beta}(\omega)\) associated with each system-environment interaction term.

To simplify the numerical implementation we assume that \(A_\alpha\) are Hermitian and that cross-correlations between different environment operators vanish, so that the final expression for the Bloch-Redfield tensor that is implemented in QuTiP is

Bloch-Redfield master equation in QuTiP¶

In QuTiP, the Bloch-Redfield tensor Eq. (7) can be calculated using the function qutip.bloch_redfield.bloch_redfield_tensor. It takes two mandatory arguments: The system Hamiltonian \(H\), a nested list of operator \(A_\alpha\), spectral density functions \(S_\alpha(\omega)\) pairs that characterize the coupling between system and bath. The spectral density functions are Python callback functions that takes the (angular) frequency as a single argument.

To illustrate how to calculate the Bloch-Redfield tensor, let’s consider a two-level atom

that couples to an Ohmic bath through the \(\sigma_x\) operator. The corresponding Bloch-Redfield tensor can be calculated in QuTiP using the following code

In [1]: delta = 0.2 * 2*np.pi; eps0 = 1.0 * 2*np.pi; gamma1 = 0.5

In [2]: H = - delta/2.0 * sigmax() - eps0/2.0 * sigmaz()

In [3]: def ohmic_spectrum(w):

...: if w == 0.0: # dephasing inducing noise

...: return gamma1

...: else: # relaxation inducing noise

...: return gamma1 / 2 * (w / (2 * np.pi)) * (w > 0.0)

...:

In [4]: R, ekets = bloch_redfield_tensor(H, [[sigmax(), ohmic_spectrum]])

In [5]: R

Out[5]:

Quantum object: dims = [[[2], [2]], [[2], [2]]], shape = (4, 4), type = super, isherm = False

Qobj data =

[[ 0. +0.j 0. +0.j 0. +0.j

0.24514517+0.j ]

[ 0. +0.j -0.16103412-6.4076169j 0. +0.j

0. +0.j ]

[ 0. +0.j 0. +0.j -0.16103412+6.4076169j

0. +0.j ]

[ 0. +0.j 0. +0.j 0. +0.j

-0.24514517+0.j ]]

Note that it is also possible to add Lindblad dissipation superoperators in the Bloch-Refield tensor by passing the operators via the c_ops keyword argument like you would in the qutip.mesolve or qutip.mcsolve functions. For convenience, the function qutip.bloch_redfield.bloch_redfield_tensor also returns a list of eigenkets ekets, since they are calculated in the process of calculating the Bloch-Redfield tensor R, and the ekets are usually needed again later when transforming operators between the computational basis and the eigenbasis.

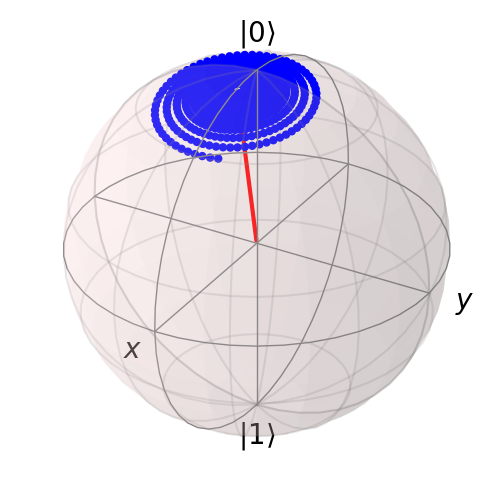

The evolution of a wavefunction or density matrix, according to the Bloch-Redfield master equation (5), can be calculated using the QuTiP function qutip.bloch_redfield.bloch_redfield_solve. It takes five mandatory arguments: the Bloch-Redfield tensor R, the list of eigenkets ekets, the initial state psi0 (as a ket or density matrix), a list of times tlist for which to evaluate the expectation values, and a list of operators e_ops for which to evaluate the expectation values at each time step defined by tlist. For example, to evaluate the expectation values of the \(\sigma_x\), \(\sigma_y\), and \(\sigma_z\) operators for the example above, we can use the following code:

In [6]: import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

In [7]: tlist = np.linspace(0, 15.0, 1000)

In [8]: psi0 = rand_ket(2)

In [9]: e_ops = [sigmax(), sigmay(), sigmaz()]

In [10]: expt_list = bloch_redfield_solve(R, ekets, psi0, tlist, e_ops)

In [11]: sphere = Bloch()

In [12]: sphere.add_points([expt_list[0], expt_list[1], expt_list[2]])

In [13]: sphere.vector_color = ['r']

In [14]: sphere.add_vectors(np.array([delta, 0, eps0]) / np.sqrt(delta ** 2 + eps0 ** 2))

In [15]: sphere.make_sphere()

In [16]: plt.show()

The two steps of calculating the Bloch-Redfield tensor and evolving according to the corresponding master equation can be combined into one by using the function qutip.bloch_redfield.brmesolve, which takes same arguments as qutip.mesolve and qutip.mcsolve, save for the additional nested list of operator-spectrum pairs that is called a_ops.

In [17]: output = brmesolve(H, psi0, tlist, a_ops=[[sigmax(),ohmic_spectrum]], e_ops=e_ops)

where the resulting output is an instance of the class qutip.solver.Result.

Time-dependent Bloch-Redfield Dynamics¶

Note

New in QuTiP 4.2.

Warning

It takes ~3-5 seconds (~30 if using Visual Studio) to compile a time-dependent Bloch-Redfield problem. Therefore,

if you are doing repeated simulations by varying parameters, then it is best to pass

options = Options(rhs_reuse=True) to the solver.

If you have not done so already, please read the section: Solving Problems with Time-dependent Hamiltonians.

As we have already discussed, the Bloch-Redfield master equation requires transforming into the eigenbasis of the system Hamiltonian. For time-independent systems, this transformation need only be done once. However, for time-dependent systems, one must move to the instantaneous eigenbasis at each time-step in the evolution, thus greatly increasing the computational complexity of the dynamics. In addition, the requirement for computing all the eigenvalues severely limits the scalability of the method. Fortunately, this eigen decomposition occurs at the Hamiltonian level, as opposed to the super-operator level, and thus, with efficient programming, one can tackle many systems that are commonly encountered.

The time-dependent Bloch-Redfield solver in QuTiP relies on the efficient numerical computations afforded by the string-based time-dependent format, and Cython compilation. As such, all the time-dependent terms, and noise power spectra must be expressed in the string format. To begin, lets consider the previous example, but formatted to call the time-dependent solver:

In [18]: ohmic = "{gamma1} / 2.0 * (w / (2 * pi)) * (w > 0.0)".format(gamma1=gamma1)

In [19]: output = brmesolve(H, psi0, tlist, a_ops=[[sigmax(),ohmic]], e_ops=e_ops)

Although the problem itself is time-independent, the use of a string as the noise power spectrum tells the solver to go into time-dependent mode. The string is nearly identical to the Python function format, except that we replaced np.pi with pi to avoid calling Python in our Cython code, and we have hard coded the gamma1 argument into the string as limitations prevent passing arguments into the time-dependent Bloch-Redfield solver.

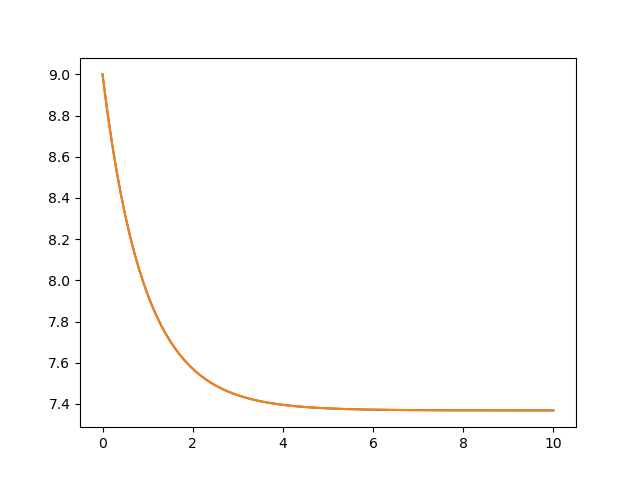

For actual time-dependent Hamiltonians, the Hamiltonian itself can be passed into the solver like any other string-based Hamiltonian, as thus we will not discuss this topic further. Instead, here the focus is on time-dependent bath coupling terms. To this end, suppose that we have a dissipative harmonic oscillator, where the white-noise dissipation rate decreases exponentially with time \(\kappa(t) = \kappa(0)\exp(-t)\). In the Lindblad or monte-carlo solvers, this could be implemented as a time-dependent collapse operator list c_ops = [[a, 'sqrt(kappa*exp(-t))']]. In the Bloch-Redfield solver, the bath coupling terms must be Hermitian. As such, in this example, our coupling operator is the position operator a+a.dag(). In addition, we do not need the sqrt operation that occurs in the c_ops definition. The complete example, and comparison to the analytic expression is:

In [20]: N = 10 # number of basis states to consider

In [21]: a = destroy(N)

In [22]: H = a.dag() * a

In [23]: psi0 = basis(N, 9) # initial state

In [24]: kappa = 0.2 # coupling to oscillator

In [25]: a_ops = [[a+a.dag(), '{kappa}*exp(-t)*(w>=0)'.format(kappa=kappa)]]

In [26]: tlist = np.linspace(0, 10, 100)

In [27]: out = brmesolve(H, psi0, tlist, a_ops, e_ops=[a.dag() * a])

In [28]: actual_answer = 9.0 * np.exp(-kappa * (1.0 - np.exp(-tlist)))

In [29]: plt.figure()

Out[29]: <Figure size 640x480 with 0 Axes>

In [30]: plt.plot(tlist, out.expect[0])

Out[30]: [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a251955c0>]

In [31]: plt.plot(tlist, actual_answer)

Out[31]: [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a254cc860>]

In [32]: plt.show()

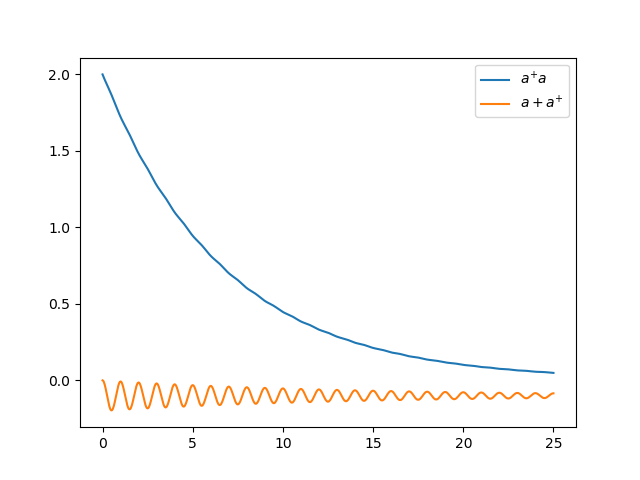

In many cases, the bath-coupling operators can take the form \(A = f(t)a + f(t)^* a^{+}\). In this case, the above format for inputting the a_ops is not sufficient. Instead, one must construct a nested-list of tuples to specify this time-dependence. For example consider a white-noise bath that is coupled to an operator of the form exp(1j*t)*a + exp(-1j*t)* a.dag(). In this example, the a_ops list would be:

In [33]: a_ops = [ [ (a, a.dag()), ('{0} * (w >= 0)'.format(kappa), 'exp(1j*t)', 'exp(-1j*t)') ] ]

where the first tuple element (a, a.dag()) tells the solver which operators make up the full Hermitian coupling operator. The second tuple ('{0} * (w >= 0)'.format(kappa), 'exp(1j*t)', 'exp(-1j*t)'), gives the noise power spectrum, and time-dependence of each operator. Note that the noise spectrum must always come first in this second tuple. A full example is:

In [34]: N = 10

In [35]: w0 = 1.0 * 2 * np.pi

In [36]: g = 0.05 * w0

In [37]: kappa = 0.15

In [38]: times = np.linspace(0, 25, 1000)

In [39]: a = destroy(N)

In [40]: H = w0 * a.dag() * a + g * (a + a.dag())

In [41]: psi0 = ket2dm((basis(N, 4) + basis(N, 2) + basis(N, 0)).unit())

In [42]: a_ops = [[ (a, a.dag()), ('{0} * (w >= 0)'.format(kappa), 'exp(1j*t)', 'exp(-1j*t)') ]]

In [43]: e_ops = [a.dag() * a, a + a.dag()]

In [44]: res_brme = brmesolve(H, psi0, times, a_ops, e_ops)

In [45]: plt.figure()

Out[45]: <Figure size 640x480 with 0 Axes>

In [46]: plt.plot(times,res_brme.expect[0], label=r'$a^{+}a$')

Out[46]: [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a24dff668>]

In [47]: plt.plot(times,res_brme.expect[1], label=r'$a+a^{+}$')

Out[47]: [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a24dffc50>]

In [48]: plt.legend()

Out[48]: <matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x1a21f86eb8>

In [49]: plt.show()

Further examples on time-dependent Bloch-Redfield simulations can be found in the online tutorials.