Quantum Optimal Control¶

Introduction¶

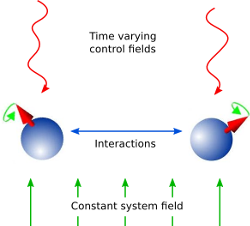

In quantum control we look to prepare some specific state, effect some state-to-state transfer, or effect some transformation (or gate) on a quantum system. For a given quantum system there will always be factors that effect the dynamics that are outside of our control. As examples, the interactions between elements of the system or a magnetic field required to trap the system. However, there may be methods of affecting the dynamics in a controlled way, such as the time varying amplitude of the electric component of an interacting laser field. And so this leads to some questions; given a specific quantum system with known time-independent dynamics generator (referred to as the drift dynamics generators) and set of externally controllable fields for which the interaction can be described by control dynamics generators:

What states or transformations can we achieve (if any)?

What is the shape of the control pulse required to achieve this?

These questions are addressed as controllability and quantum optimal control [dAless08]. The answer to question of controllability is determined by the commutability of the dynamics generators and is formalised as the Lie Algebra Rank Criterion and is discussed in detail in [dAless08]. The solutions to the second question can be determined through optimal control algorithms, or control pulse optimisation.

Schematic showing the principle of quantum control.¶

Quantum Control has many applications including NMR, quantum metrology, control of chemical reactions, and quantum information processing.

To explain the physics behind these algorithms we will first consider only finite-dimensional, closed quantum systems.

Closed Quantum Systems¶

In closed quantum systems the states can be represented by kets, and the transformations on these states are unitary operators. The dynamics generators are Hamiltonians. The combined Hamiltonian for the system is given by

where \(H_0\) is the drift Hamiltonian and the \(H_j\) are the control Hamiltonians. The \(u_j\) are time varying amplitude functions for the specific control.

The dynamics of the system are governed by Schrödingers equation.

Note we use units where \(\hbar=1\) throughout. The solutions to Schrödinger’s equation are of the form:

where \(\psi_0\) is the state of the system at \(t=0\) and \(U(t)\) is a unitary operator on the Hilbert space containing the states. \(U(t)\) is a solution to the Schrödinger operator equation

We can use optimal control algorithms to determine a set of \(u_j\) that will drive our system from \(\ket{\psi_0}\) to \(\ket{\psi_1}\), this is state-to-state transfer, or drive the system from some arbitary state to a given state \(\ket{\psi_1}\), which is state preparation, or effect some unitary transformation \(U_{target}\), called gate synthesis. The latter of these is most important in quantum computation.

The GRAPE algorithm¶

The GRadient Ascent Pulse Engineering was first proposed in [NKanej]. Solutions to Schrödinger’s equation for a time-dependent Hamiltonian are not generally possible to obtain analytically. Therefore, a piecewise constant approximation to the pulse amplitudes is made. Time allowed for the system to evolve \(T\) is split into \(M\) timeslots (typically these are of equal duration), during which the control amplitude is assumed to remain constant. The combined Hamiltonian can then be approximated as:

where \(k\) is a timeslot index, \(j\) is the control index, and \(N\) is the number of controls. Hence \(t_k\) is the evolution time at the start of the timeslot, and \(u_{jk}\) is the amplitude of control \(j\) throughout timeslot \(k\). The time evolution operator, or propagator, within the timeslot can then be calculated as:

where \(\Delta t_k\) is the duration of the timeslot. The evolution up to (and including) any timeslot \(k\) (including the full evolution \(k=M\)) can the be calculated as

If the objective is state-to-state transfer then \(X_0=\ket{\psi_0}\) and the target \(X_{targ}=\ket{\psi_1}\), for gate synthesis \(X_0 = U(0) = \mathbb{1}\) and the target \(X_{targ}=U_{targ}\).

A figure of merit or fidelity is some measure of how close the evolution is to the target, based on the control amplitudes in the timeslots. The typical figure of merit for unitary systems is the normalised overlap of the evolution and the target.

where \(d\) is the system dimension. In this figure of merit the absolute value is taken to ignore any differences in global phase, and \(0 \le f \le 1\). Typically the fidelity error (or infidelity) is more useful, in this case defined as \(\varepsilon = 1 - f_{PSU}\). There are many other possible objectives, and hence figures of merit.

As there are now \(N \times M\) variables (the \(u_{jk}\)) and one parameter to minimise \(\varepsilon\), then the problem becomes a finite multi-variable optimisation problem, for which there are many established methods, often referred to as ‘hill-climbing’ methods. The simplest of these to understand is that of steepest ascent (or descent). The gradient of the fidelity with respect to all the variables is calculated (or approximated) and a step is made in the variable space in the direction of steepest ascent (or descent). This method is a first order gradient method. In two dimensions this describes a method of climbing a hill by heading in the direction where the ground rises fastest. This analogy also clearly illustrates one of the main challenges in multi-variable optimisation, which is that all methods have a tendency to get stuck in local maxima. It is hard to determine whether one has found a global maximum or not - a local peak is likely not to be the highest mountain in the region. In quantum optimal control we can typically define an infidelity that has a lower bound of zero. We can then look to minimise the infidelity (from here on we will only consider optimising for infidelity minima). This means that we can terminate any pulse optimisation when the infidelity reaches zero (to a sufficient precision). This is however only possible for fully controllable systems; otherwise it is hard (if not impossible) to know that the minimum possible infidelity has been achieved. In the hill walking analogy the step size is roughly fixed to a stride, however, in computations the step size must be chosen. Clearly there is a trade-off here between the number of steps (or iterations) required to reach the minima and the possibility that we might step over a minima. In practice it is difficult to determine an efficient and effective step size.

The second order differentials of the infidelity with respect to the variables can be used to approximate the local landscape to a parabola. This way a step (or jump) can be made to where the minima would be if it were parabolic. This typically vastly reduces the number of iterations, and removes the need to guess a step size. The method where all the second differentials are calculated explicitly is called the Newton-Raphson method. However, calculating the second-order differentials (the Hessian matrix) can be computationally expensive, and so there are a class of methods known as quasi-Newton that approximate the Hessian based on successive iterations. The most popular of these (in quantum optimal control) is the Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno algorithm (BFGS). The default method in the QuTiP Qtrl GRAPE implementation is the L-BFGS-B method in Scipy, which is a wrapper to the implementation described in [Byrd95]. This limited memory and bounded method does not need to store the entire Hessian, which reduces the computer memory required, and allows bounds to be set for variable values, which considering these are field amplitudes is often physical.

The pulse optimisation is typically far more efficient if the gradients can be calculated exactly, rather than approximated. For simple fidelity measures such as \(f_{PSU}\) this is possible. Firstly the propagator gradient for each timeslot with respect to the control amplitudes is calculated. For closed systems, with unitary dynamics, a method using the eigendecomposition is used, which is efficient as it is also used in the propagator calculation (to exponentiate the combined Hamiltonian). More generally (for example open systems and symplectic dynamics) the Frechet derivative (or augmented matrix) method is used, which is described in [Flo12]. For other optimisation goals it may not be possible to calculate analytic gradients. In these cases it is necessary to approximate the gradients, but this can be very expensive, and can lead to other algorithms out-performing GRAPE.

The CRAB Algorithm¶

It has been shown [Lloyd14], the dimension of a quantum optimal control problem is a polynomial function of the dimension of the manifold of the time-polynomial reachable states, when allowing for a finite control precision and evolution time. You can think of this as the information content of the pulse (as being the only effective input) being very limited e.g. the pulse is compressible to a few bytes without loosing the target.

This is where the Chopped RAndom Basis (CRAB) algorithm [Doria11], [Caneva11] comes into play: Since the pulse complexity is usually very low, it is sufficient to transform the optimal control problem to a few parameter search by introducing a physically motivated function basis that builds up the pulse. Compared to the number of time slices needed to accurately simulate quantum dynamics (often equals basis dimension for Gradient based algorithms), this number is lower by orders of magnitude, allowing CRAB to efficiently optimize smooth pulses with realistic experimental constraints. It is important to point out, that CRAB does not make any suggestion on the basis function to be used. The basis must be chosen carefully considered, taking into account a priori knowledge of the system (such as symmetries, magnitudes of scales,…) and solution (e.g. sign, smoothness, bang-bang behavior, singularities, maximum excursion or rate of change,….). By doing so, this algorithm allows for native integration of experimental constraints such as maximum frequencies allowed, maximum amplitude, smooth ramping up and down of the pulse and many more. Moreover initial guesses, if they are available, can (however not have to) be included to speed up convergence.

As mentioned in the GRAPE paragraph, for CRAB local minima arising from algorithmic design can occur, too. However, for CRAB a ‘dressed’ version has recently been introduced [Rach15] that allows to escape local minima.

For some control objectives and/or dynamical quantum descriptions, it is either not possible to derive the gradient for the cost functional with respect to each time slice or it is computationally expensive to do so. The same can apply for the necessary (reverse) propagation of the co-state. All this trouble does not occur within CRAB as those elements are not in use here. CRAB, instead, takes the time evolution as a black-box where the pulse goes as an input and the cost (e.g. infidelity) value will be returned as an output. This concept, on top, allows for direct integration in a closed loop experimental environment where both the preliminarily open loop optimization, as well as the final adoption, and integration to the lab (to account for modeling errors, experimental systematic noise, …) can be done all in one, using this algorithm.

Optimal Quantum Control in QuTiP¶

There are two separate implementations of optimal control inside QuTiP. The first is an implementation of first order GRAPE, and is not further described here, but there are the example notebooks. The second is referred to as Qtrl (when a distinction needs to be made) as this was its name before it was integrated into QuTiP. Qtrl uses the Scipy optimize functions to perform the multi-variable optimisation, typically the L-BFGS-B method for GRAPE and Nelder-Mead for CRAB. The GRAPE implementation in Qtrl was initially based on the open-source package DYNAMO, which is a MATLAB implementation, and is described in [DYNAMO]. It has since been restructured and extended for flexibility and compatibility within QuTiP.

The rest of this section describes the Qtrl implementation and how to use it.

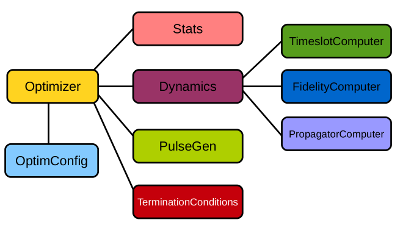

- Object Model

The Qtrl code is organised in a hierarchical object model in order to try and maximise configurability whilst maintaining some clarity. It is not necessary to understand the model in order to use the pulse optimisation functions, but it is the most flexible method of using Qtrl. If you just want to use a simple single function call interface, then jump to Using the pulseoptim functions

Qtrl code object model.¶

The object’s properties and methods are described in detail in the documentation, so that will not be repeated here.

- OptimConfig

The OptimConfig object is used simply to hold configuration parameters used by all the objects. Typically this is the subclass types for the other objects and parameters for the users specific requirements. The

loadparamsmodule can be used read parameter values from a configuration file.- Optimizer

This acts as a wrapper to the

Scipy.optimizefunctions that perform the work of the pulse optimisation algorithms. Using the main classes the user can specify which of the optimisation methods are to be used. There are subclasses specifically for the BFGS and L-BFGS-B methods. There is another subclass for using the CRAB algorithm.- Dynamics

This is mainly a container for the lists that hold the dynamics generators, propagators, and time evolution operators in each timeslot. The combining of dynamics generators is also complete by this object. Different subclasses support a range of types of quantum systems, including closed systems with unitary dynamics, systems with quadratic Hamiltonians that have Gaussian states and symplectic transforms, and a general subclass that can be used for open system dynamics with Lindbladian operators.

- PulseGen

There are many subclasses of pulse generators that generate different types of pulses as the initial amplitudes for the optimisation. Often the goal cannot be achieved from all starting conditions, and then typically some kind of random pulse is used and repeated optimisations are performed until the desired infidelity is reached or the minimum infidelity found is reported. There is a specific subclass that is used by the CRAB algorithm to generate the pulses based on the basis coefficients that are being optimised.

- TerminationConditions

This is simply a convenient place to hold all the properties that will determine when the single optimisation run terminates. Limits can be set for number of iterations, time, and of course the target infidelity.

- Stats

Performance data are optionally collected during the optimisation. This object is shared to a single location to store, calculate and report run statistics.

- FidelityComputer

The subclass of the fidelity computer determines the type of fidelity measure. These are closely linked to the type of dynamics in use. These are also the most commonly user customised subclasses.

- PropagatorComputer

This object computes propagators from one timeslot to the next and also the propagator gradient. The options are using the spectral decomposition or Frechet derivative, as discussed above.

- TimeslotComputer

Here the time evolution is computed by calling the methods of the other computer objects.

- OptimResult

The result of a pulse optimisation run is returned as an object with properties for the outcome in terms of the infidelity, reason for termination, performance statistics, final evolution, and more.

Using the pulseoptim functions¶

The simplest method for optimising a control pulse is to call one of the functions in the pulseoptim module. This automates the creation and configuration of the necessary objects, generation of initial pulses, running the optimisation and returning the result. There are functions specifically for unitary dynamics, and also specifically for the CRAB algorithm (GRAPE is the default). The optimise_pulse function can in fact be used for unitary dynamics and / or the CRAB algorithm, the more specific functions simply have parameter names that are more familiar in that application.

A semi-automated method is to use the create_optimizer_objects function to generate and configure all the objects, then manually set the initial pulse and call the optimisation. This would be more efficient when repeating runs with different starting conditions.